Power & Place

Even today, centuries after the collapse of Khmer empire, Angkor Wat endures as a striking symbol of power and authority. It has outlasted the rulers of the Khmer Empire and has become intertwined with notions of Cambodian nationhood and identity.

A Living City

The city of Angkor is perhaps best known today for the extensive network of stone temples that dot the Cambodian landscape. Although enormously impressive structures, they are not the sum total of the city as it existed in the thirteenth century. Instead, they form the religious skeleton of what was once a living city. The stone remains of Angkor have been the subject of extensive scholarship, but recent archaeological surveys have unearthed evidence of large numbers of wooden dwellings that lay within Angkor Wat’s extensive temple complex and which are thought to have been home to thousands of Angkor Wat’s massive workforce.

“The great medieval settlement of Angkor in Cambodia [9th–16th centuries Common Era (CE)] has for many years been understood as a ‘‘hydraulic city,’’ an urban complex defined, sustained, and ultimately overwhelmed by a complex water management network. Since the 1980s that view has been disputed, but the debate has remained unresolved because of insufficient data on the landscape beyond the great temples: the broader context of the monumental remains was only partially understood and had not been adequately mapped. Since the 1990s, French, Australian, and Cambodian teams have sought to address this empirical deficit through archaeological mapping projects by using traditional methods such as ground survey in conjunction with advanced radar remote-sensing applications in partnership with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)/Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). Here we present a major outcome of that research: a comprehensive archaeological map of greater Angkor, covering nearly 3,000 km2, prepared by the Greater Angkor Project (GAP). The map reveals a vast, low-density settlement landscape integrated by an elaborate water management network covering >1,000 km2, the most extensive urban complex of the preindustrial world. It is now clear that anthropogenic changes to the landscape were both extensive and substantial enough to have created grave challenges to the long-term viability of the settlement.” (Evans et al. 2007, 14277)

Questions

Does this video square with your impression of Angkor Wat? What kind of structures do you see in the video? Why are such structures absent today?

Using what you learned from the module on water and climate, think about the patterns of settlement identified by Evans et al. Why was Angkor set out the way it was?

How do different building materials reflect the different uses for buildings?

Greater Angkor has been described as a “low-density urban complex”. What does this mean? How was the city set up? Why do you think this was the case? Does this remind you of any other cities?

Colour and History

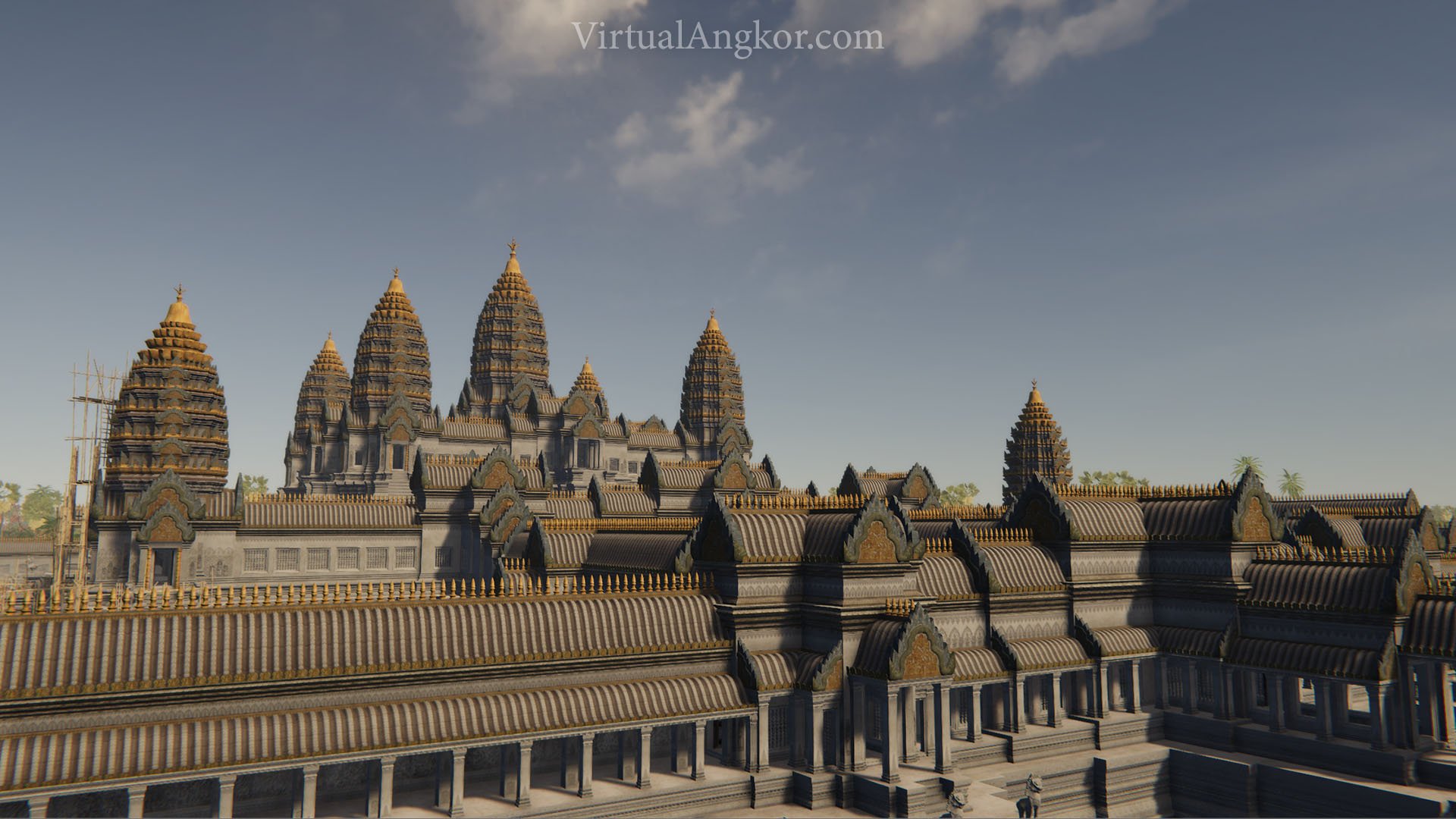

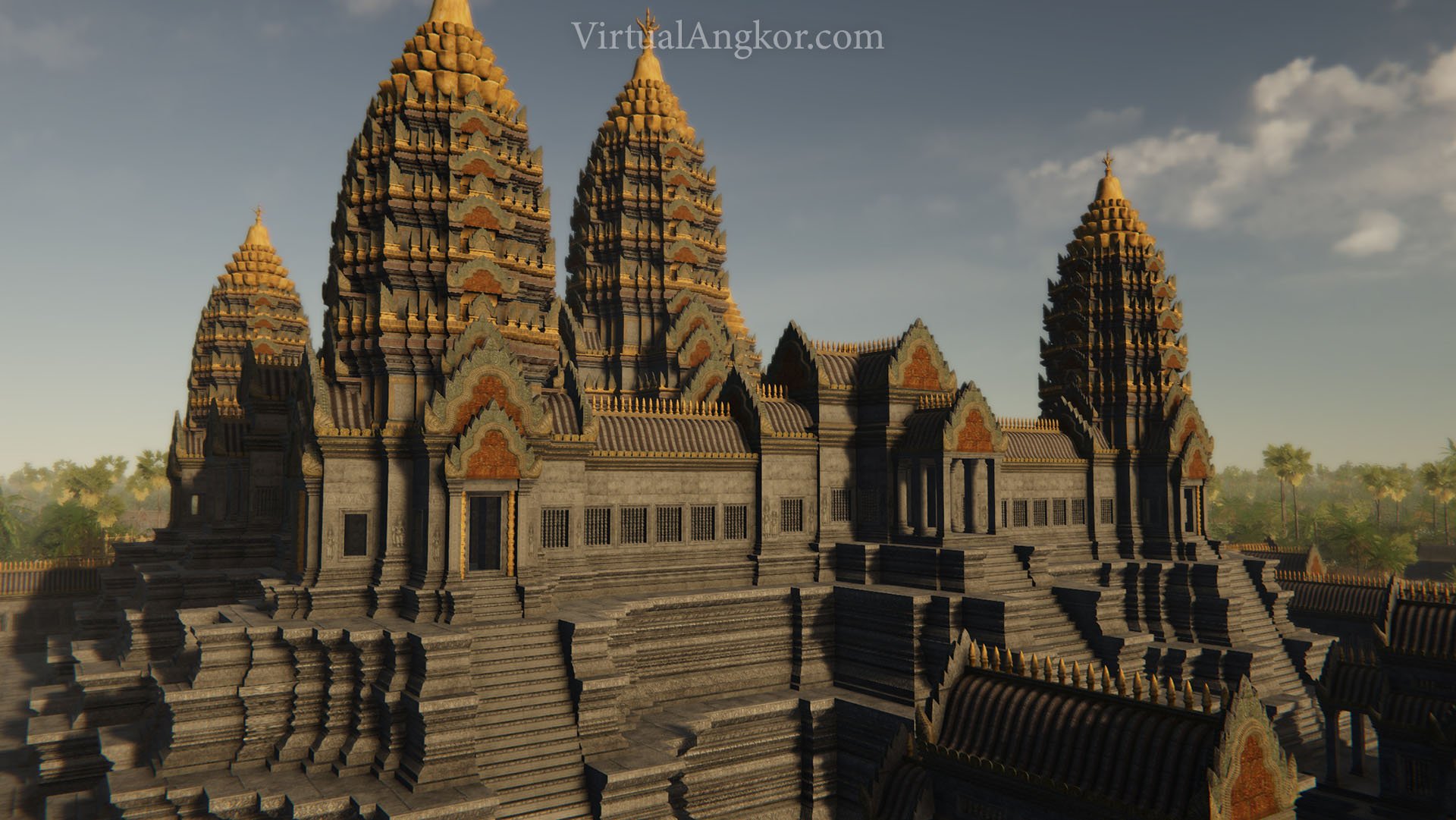

In their current form, the temples of Angkor are largely monochrome monuments of grey, broken up only by splashes of green as nature encroaches upon the ancient city. In the thirteenth century, however, things looked very different as the city was dominated by brightly coloured, elaborately decorated temples that spread out across the landscape.

“In the center of the capital is a gold tower [Bayon], flanked by twenty or so stone towers and a hundred or so stone chambers. To the east of it is a golden bridge flanked by two gold lions, one on the left and one on the right. Eight gold Buddhas are laid out in a row at the lowest level of stone chambers.

About a li north of the gold tower there is a bronze tower [Bapuon]. It is even taller than the gold tower, and an exquisite sight. At the foot there are, again, several dozen stone chambers…

Ten li east of the city wall lies the East Lake [East Baray]. It is about a hundred li in circumference. In the middle of it there is a stone tower with stone chambers. In the middle of the tower is a bronze reclining Buddha with water constantly flowing from its navel.

Five li to the north of the city wall lies the North Lake [Jayatataka Baray]. In the middle of it is a gold tower, square in shape, with several dozen stone chambers [Neak Pean]. A gold lion, a gold Buddha, a bronze elephant, a bronze cow, and a bronze horse—these are all there” (Zhou Daguan, 47-48)

“The royal palace, officials’ residences, and great houses all face east. The palace lies to the north of the gold tower with the gold bridge [Bayon], near the northern gateway. It is about five or six li in circumference. The tiles of the main building are made of lead; all the other tiles are made of yellow clay. The beams and pillars are huge, and are all carved and painted with images of the Buddha. The rooms are really quite grand-looking, and the long corridors and complicated walkways, the soaring structures that rise and fall, all give a considerable sense of size…

Inside the palace there is a gold tower, at the summit of which the king sleeps at night…Next come the dwellings of the king’s relatives, senior officials, and so on. These are large and spacious in style, very different from ordinary people’s homes. The roofs are made entirely of thatch, except for the family shrine and the main bedroom, both of which can be tiled…At the lowest level come the homes of the common people. They only use thatch for their roofs, and dare not put up a single tile.” (Zhou Daguan, 49)

Representation of what Angkor Wat might have looked like during its heyday.

“Indeed, colour is one archaeological reality of Angkor that is seldom expressed in visual descriptions, though a National Geographic article featuring paintings by Maurice Fievet (Moore 1960) is a well known exception. In this widely published vision of Angkor as a vividly coloured living city, the illustrations paint lively scenes full of rich red, green and blue fabrics in technicolour, and a great deal of gold ornamentation. Intriguingly, these colours adorn everything but the temples which remained relegated to a uniform cement grey…

Though Zhou Daguan mentions gold towers and faces at Angkor, and there are obvious remains of plaster stucco, the physical evidence for the colouration of the temples is scant. Very little paint work or stucco has survived the centuries of the tropical climate. There is evidence of polychrome decoration and plastering inside some of the ruins, but to date no clear evidence of colour has emerged on the many thousands, if not millions, of tumbled stones in the Angkor area. In the words of Carl Sagan, absence of evidence is not necessarily evidence of absence. As a broader analogy, we might consider the eld of palaeontology, where renderings of dinosaurs have gradually evolved over the years from grey-green Victorian ‘iguanodons’ that haunt the grounds of Crystal Palace on the outskirts of London. Today popular science literature depicts dinosaurs as brightly coloured bird-like creatures, despite the lack of hard evidence.” (Chandler and Polkinghorne 2012)

Questions

Take a look at the colour schemes of the temples shown in this module on the website, what do you notice? Are there particular colours that seem to recur? Why do you think they recur?

Based on your reading of the sources above, what do you think was the role of colour in Angkor? How is it being interpreted by an outsider like Zhou Daguan?

Think about the relationship between power, colour and religion. What other examples can you think of that reflect this connection?

Architecture and Power

Power was tied closely to construction and architecture as each Khmer king built ever more extensive and elaborate temple complexes to reinforce their divine kingship and to ensure that they would be remembered for years to come. Angkor Wat was perhaps the greatest of these massive construction projects. It was also unique in the symbolic meaning weaved into its architecture.

“Angkor Wat was an elaborate ritual, iconographic and cosmological construct…Shadows in the shape of the central towers of Angkor Wat produced by the late afternoon sun shining through the carved pillars in the windows of the galleries. In many ways, from remarkable visual effects to intensely abstruse geometry. Such an effect occurs when the late afternoon sun shines through the carved pillars in the windows of the galleries, producing shadows in the shape of the central towers from the profiles of the pillars, and is repeated thousands of times down the corridors. As with other Khmer temples, the main temple is not quite symmetrical. For example, in the western and eastern frontages, the gallery on the north side has 20 pillars whereas the southern one has 18. This feature cannot be accidental. The reason for the asymmetry is unclear, although Kak (1999: 119 & 122) has proposed that an asymmetry in the axes of the central tower relates to the temporal asymmetry of the two parts of the year in Satapatha astronomy. Another proposal concerning temporal cosmology was made in the 1970s by Robert Stencel and colleagues, suggesting that the divisions between the sectors of the main western causeway of Angkor Wat correspond to the proportional duration of the successive yuga, or ages, of the Hindu cosmology (Stencel et al. 1976: 786). On a physically grander scale, the entire layout of Angkor Wat—as with all the major state temples, a pyramid mountain surrounded by a moat—is considered to correspond with the cosmology of Mount Meru and the surrounding Sea of Milk from which ambrosia was churned by the gods and demons.

Beyond the immediate vicinity of the temple, Angkor Wat was also enmeshed within the cosmology and symbolism of the urban landscape and the water network . Two shrines of the Angkor Wat style, Thommanon and Chau Say Tevoda, lie on either side of the east–west axial road between the Royal Palace and the East Baray. Farther east, the shrine of Banteay Samre was located at the south-east corner of the East Baray, and beyond the baray, the road to the east continues through another shrine in the style of Angkor Wat at Chau Srei Vibol, which forms an eastern boundary to Greater Angkor. To the west, the great reclining statue of Vishnu, which was located on the West Mebon in the middle of the West Baray, is known to have superseded an earlier configuration consisting of a large, upright, cylindrical stone column. The statue, which is conventionally ascribed to the mid-eleventh century because of its Baphuon style, may instead have been emplaced in the early twelfth century as part of a resumption of the ritual and water management landscape in the reign of Suryavaraman II. Not only was Angkor Wat an immense ritual construction, it was integral to the presentation of power in Angkor and, also, to the operation of the water network and hence urban landscape of Greater Angkor. The moat of Angkor Wat now has a channel associated with its eastern causeway and three others through the northern edge of the moat, indicating connections to both the eastern and western parts of the water network, stretching across Greater Angkor. At the south-west corner of the moat, a canal runs for more than 13km from north–south, crossing the entire southern half of Greater Angkor down to the potential port site at Phnom Krom on the edge of the great lake, the Tonle Sap.” (Fletcher et al. 2015, 1395—1396)

Questions

Note the sheer size and scale of Angkor Wat. What does Angkor Wat tell us about the development of the Khmer Empire? What does this tell us about Suryavarman II, the king that commissioned the construction of the temple?

What theories have scholars advanced about the broader meaning and implications of Angkor Wat’s architecture?

What was the relationship between architecture, religion and power in twelfth century Angkor?

Consider the symbolic power of grand construction projects like Angkor Wat. Can you think of any parallels?

Scholars have described Angkor Wat as “an elaborate ritual, iconographic and cosmological construct.” What evidence can you find for this in the article?

Power and Place Image Gallery

Further Reading

Chandler, Tom and Martin Polkinghorne. “Through the Visualisation Lens: Temple Models and Simulated Context in a Virtual Angkor.” In Old Myths and New Approaches: Interpreting Religious Sites in Southeast Asia, 211–229. Edited by Alexandra Haendel. Clayton, Victoria: Monash University Publishing, 2012.

Daguan, Zhou. “The City and Its Walls” and “Residences.” In A Record of Cambodia: The Land and Its People, 47–49. Translated by Peter Harris. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, 2007.

Evans, Damian, Christophe Pottier, Roland Fletcher, Scott Hensley, Ian Tapley, Anthony Milne and Michael Barbetti. “A Comprehensive Archaeological Map of the World’s Largest Preindustrial Settlement Complex at Angkor, Cambodia.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104, no. 36 (2007): 14277-14282.

Fletcher, Roland, Damian Evans, Christophe Pottier, and Chhay Rachna. “Angkor Wat: An Introduction.” Antiquity 89 no. 348 (December 2015). 1388–1401.